It's Time to Sow Your Seeds

/Learn how to grow plants from seed—yes, even in Central Oregon.

Read MoreLearn how to grow plants from seed—yes, even in Central Oregon.

Read MoreLike coronavirus, knapweed is a scourge. Unlike the virus, you can see it and defeat it.

Read MoreThese are scary times we’re living in, and I’m finding that my requirements shift almost by the hour, from needing to soak up the latest facts to needing to “socially distance” myself from the news through laughter and silliness.

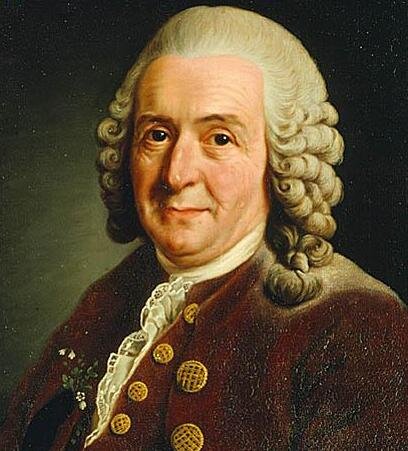

When and if you fall into the latter camp, this blog is for you. It’s a follow-up to my previous blog, where I listed some wonderfully odd and often humorous facts about Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish scientist and sometimes-awful human who came up with binomial nomenclature (naming species by a genus and species, like Canis lupus for wolves).

I’ll get back to talking about nature in a more direct way in future blogs, but for now I hope these eight stories provide a pleasant diversion.

Aristotle thought that since plants don’t move, they don’t have sex. Linnaeus put an end to that nonsense. He showed that flowers have sexual organs called pistils and stamens. “Yes, love comes even to the plants,” he wrote.

As Oliver Sacks put it, Linnaeus “made merry with the idea” of sexual organs in plants. Linnaeus wrote an essay called “Introduction to the Betrothal of Plants” and talked about stamens as husbands, pistils as wives, and the calyx as the nuptial bed. Here’s one of his steamy passages:

The flower’s leaves … serve as bridal beds which the creator has so gloriously arranged … and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much greater solemnity. When now the bed is so prepared, it is time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and offer her his gifts.

A trillium showing off its reproductive parts. Photo: M.A. Willson

As you might imagine, some people were titillated by all this plant sex talk, which led to an increased interest in botany (seriously). Also as you might imagine, other people clutched their pearls. One critic said, “Such loathsome harlotry as several males to one female would never have been permitted in the vegetable kingdom by the Creator.”

As it turns out, such “harlotry” is not only permitted but quite commonplace across the natural world.

Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus was so inspired by Linnaeus’s ideas about the sex lives of plants that he penned a couple long poems published together as The Botanic Garden (1789). His book was a bestseller that created an uproar because of its sexually explicit passages. The book also included a hint of Erasmus’s belief in evolution, long before his grandson’s revelations on the subject.

Another favorite story about Erasmus: He was a doctor by trade but also a brilliant inventor of, among other things, a copying machine, a canal lift for barges, and a steering mechanism for carriages that was later adapted for cars.

But my very favorite invention? Erasmus grew so rotund that he had a semi-circle cut out of his place at the dinner table so he could sit closer to the food.

In Oregon, we’ll soon see tree, cliff, and other swallows swooping and swerving over waterways. Where have they been since fall? We now know that they migrate south where there are insects to feed on through the cold months. But for his whole life, Linnaeus believed that swallows slept through winter at the bottom of lakes.

Barn swallow. Photo: John Williams

More specifically, Linnaeus believed that swallows gathered in large groups, then dove under a sheet of ice where they slept, gills be damned, until spring came along and they thawed out. This was common folklore at the time, as it seemed impossible that birds could fly thousands of miles twice a year—which is, indeed, an astounding feat.

Linnaeus knew more about plants than he did about animals, and despite his claims to fame, he was a pretty crummy scientist overall. Case in point: Obviously without evidence, he thought that you could turn a puppy into a dwarf by rubbing the puppy’s back with a flavored spirit called aquavit. If you’re really, really bored during the pandemic, you’re free to try this.

Linnaeus also thought that rattlesnakes used the intensity of their gaze to bewitch birds and squirrels, causing them to fall from trees into the snake’s mouth.

Linnaeus was the first to use the word fauna (meaning animals) as the counterpart to flora (plants). Fauna is a feminine version of Faunus, the name of a Roman forest god.

Linnaeus is a beloved national hero in Sweden, where his face is on the 100 kronor note and his favorite flower, the twinflower (Linnaea borealis), appears on the 20 kronor note. If you read the first blog, you won’t be surprised to hear that Linnaeus named twinflower after himself.

The circle with the arrow for male and the circle with a cross below it for female? You can thank Linnaeus for them. The symbols had been used by chemists (the male symbol referred to Mars and iron; the female to Venus and copper), but Linnaeus was the first to use them as symbols for male and female species.

In 1732, when Linnaeus was 25, he traveled from Uppsala, near Stockholm, to an area called Swedish Lapland, the northernmost region of Sweden. He kept a detailed, illustrated journal of the plants and animals he saw on his five-month trip.

When he got back to Uppsala, Linnaeus exaggerated the whole experience. First, he said he had traveled 4,500 miles, which was about double the miles he actually traversed. The poor and famously stingy Linnaeus was being paid by the mile, so that might be why he drew an entirely fictionalized inland leg on his map.

Linnaeus also exaggerated the hardships he endured on his epic journey. A historian named Lisbet Koerner estimates that Linnaeus only spent 18 days of his five-month journey sleeping outside homes or on the coast. Which reminds me of Henry David Thoreau, whose “hardships” at Walden Pond included having his mom do his laundry and bring him sandwiches.

That’s all for now, folks. Please take care of yourself during this difficult time, and spread love to others however you can.

Look, I know how nerdy this sounds, but Carl Linnaeus makes me laugh. Yes, I’m talking about the 18th century botanist most famous for coming up with the system we use to name plants and animals.

I’ve been doing some research into Linnaeus that has distracted me from reading more than necessary about the coronavirus, the global economy, political infighting, and toilet paper shortages.

I hope that these seven fascinating, strange, and flat-out funny stories about a quirky, misguided scientist will likewise give you a reprieve from the darker stories of the day.

Linnaeus did a helpful thing in coming up with binomial nomenclature, but he was a deeply, deeply flawed person and scientist. I highly recommend reading Jason Roberts's book Every Living Thing to learn more about Linnaeus and his skulduggery.

But in this little blog I'm focused on some of the funny stuff from Linnaues, so let's enjoy the fact that he described amphibians as “these most terrible and vile animals.” He listed their attributes as: “ghastly color, cartilaginous skeleton, foul skin, fierce face, a meditative gaze, a foul odor, a harsh call, a squalid habitat, and terrible venom.” See what I mean? He HATED amphibians.

An “unsightly” treefrog. Photo: Alan St. John

Linnaeus loved to categorize things (rather obviously, since that was his life's work), and he did so using some humorous analogies.

At one point he compares animals to an infantry: Mammals are foot soldiers dressed in furs, birds are cavalry beautifully clothed in dyed down. Amphibians? They're “an unsightly, hideous naked mob, with no uniforms, inadequately armed except some who got terrifying poisoned darts.”

To be fair, Linnaeus also wrote one nice thing about amphibians: “Some [frogs] sang so beautifully that you felt newborn, and banished all disagreeable thoughts; others so mournfully that one almost dies of melancholy.” On that, at least, I think he’s right.

Linnaeus was a dangerously vengeful man, but again, let's focus on the funny angle. A German named Johann Siegesbeck was offended by Linnaeus’s work, so in response to the German’s criticism, Linnaeus named a weed that produces a nasty-smelling fluid Siegesbeckia. Likewise, when a former student of Linnaeus’s named Daniel Rolander refused to show his full plant collection to Linnaeus (so rude!), Linnaeus named a species of beetle after him, Aphanus rolandri. Just to rub it in, Aphanus means “inconspicuous.”

Linnaeus wrote four—four!—autobiographies. In those days, autobiographies were sort of like résumés, so it wasn’t unusual to write one, or maybe two, but Linnaeus wrote four, in which he admired himself in myriad ways (using third person to refer to himself):

Of returning to his fiancée, after four years away: “Travelled straight to Falun to see his beloved, who for nearly four years had been waiting for her dear Ulysses.”

Of one of his works: “the foreigners will be stunned by it.”

Of another work: It will live “in the palace of the princes of botany.”

Of his other works: They’re “masterpieces.”

On his accomplishments: “No one has been a greater botanist or zoologist.”

Before Linnaeus came up with the idea of naming things by genus and species, a wild geranium was called Geranium pedunculis bifloris caule dichotomo erecto foliis quinquepartitis incisis summis sessilibus. A particular tomato species was Solanum caule inerme herbaceo, foliis pinnatis incisis, racemis simplicibus.

I think we can agree that those names are not simplicibus at all. To make matters even more confusing, those same plants would often have entirely different names in other countries.

These naming issues increased in the 1730s, when people began to realize that the world had more than just a few thousand plant and animal species. As ships started traveling the world and returning to Sweden with “new” plant and animal species, it became evident that it was critical that we have one clear, simple naming system. That’s what Linnaeus came up with, and for that he’s justifiably renowned.

By the way, there were about 20,000 named species in Linnaeus’s time. Today there are more than 1.8 million.

This is not so funny, but it is interesting. Unlike her famous grandson, Linnaeus’s grandma was not exactly rewarded for her interest in botany. Try as I might, I haven’t been able to learn anything more than the fact that she was a botanist who was burned as a witch. It makes you think, doesn’t it, about what more women in history might have accomplished if they’d been able to pursue their interests uninhibited by discrimination and acts of violence.

We can thank Linnaeus for thousands of scientific names that still apply today. Among them is the name of our own humble species (although he separated us into four species, distinguished by woefully wrong and racist traits). Homo means “male” and sapiens means “wise,” so the first word is true only half the time and the second is true rarely, if ever, as evidenced by Linnaeus himself.

The scary thing is I’m only warming up here. I’ll post part two on Linnaeus soon. As long as we’re self-quarantining, we might as well enjoy some laughs.

(You can also read this blog, with different butterfly photos, at the Oregon Natural Desert Association’s website.)

Western Tiger Swallowtail on milkweed. Photo: Kim Elton

I wonder if butterflies might get annoyed with all the poetic language they attract. They’re “tiny rainbows,” “flying flowers,” and “ephemeral angels.” We use them as metaphors for transformation and symbols of beauty, joy, and immortality.

But what are they really?

My fear is that with all the chatter about beautiful butterflies reflecting the sky or brightening our summer days, we might overlook the astonishing truth of what they’re actually doing out there in the wild and in our backyards.

On your next hike or camping trip in Central or Eastern Oregon, when you see some of the butterflies shown here, consider the remarkable ways in which they, like us, are sensing the world.

Here’s looking at you, Cabbage White. Photo: Sue Anderson

Look at the head of a butterfly to see the two tiny compound eyes that give them a wide field of vision (yes, they see you too). They can look up, down, to the side, forward, and backward at the same time, and they can detect colors into the ultraviolet range that confounds us.

Their eyes have tens of thousands of individual light receptors—picture a honeycomb—each with its own microscopic lens. When the amount of light hitting the receptors changes, as when a predator or a net approaches, butterflies can detect the movement and take evasive action.

Juba Skippers might hear you coming. Photo: Sue Anderson

Butterfly hearing hasn’t been studied for long—there is so much about even the most common of animals that we’re still learning. But we do know that some butterflies can hear using a membrane located on their wings (or other body parts) that vibrates in response to sounds.

Some moths have ears tuned to the high-frequency echolocation calls of bats; when they hear those calls, they either take evasive action or drop to the ground as if dead. Butterfly hearing is thought to be similar, only theirs is tuned to different frequencies—like the low-frequency sound of a bird’s wings flapping as it swoops in for a meal.

This Lorquin’s Admiral smells using the tips of its antennae. Photo: Dave Rein

Butterflies have chemoreceptors similar to the ones in our noses, but theirs are located on their feet and antennae. The club-like tips of butterfly antennae are especially dense with chemoreceptors, which can sense the honey-like odor of nectar or the smell of pheromones emitted by males of some species.

Mud provides valuable minerals to these California Tortoiseshells. Photo: Sue Anderson

Butterflies touch and feel leaves, flowers, and other objects with their feet, antennae, proboscis, and tiny hairs all over their bodies.

Butterflies eat leaves and other food when they’re larvae (caterpillars), building up strength to eventually transform into adults. During their usually brief adult lives, they don’t eat anything. Instead, they drink nectar and other substances using the straw-like proboscis at the front of their heads.

They also taste leaves using chemoreceptors on their forelegs, which is especially important for female butterflies when they’re trying to find the right place to lay their eggs. Each butterfly species can only lay eggs successfully on certain host plants that provide the right nutrients—most famously, Monarchs need to lay their eggs on milkweeds.

Watch closely, and sometime you might see a butterfly drumming her legs—sometimes all six legs—on a leaf to draw out juices for the chemoreceptors on her legs to test. Only if the taste is right, indicating that the leaf is indeed that of a host plant, will she deposit one or more of her eggs.

The next time your friend remarks on a butterfly’s beauty while walking quickly past, you might stop and say, “You know, they’re more than just beautiful …” Then stay for a while. Pull out your binoculars and your field guide, so you can both identify the species and appreciate how that one individual is experiencing the world.

A Painted Lady dips her proboscis into a flower. Photo: Sue Anderson

LeeAnn Kriegh is the author of The Nature of Bend. Her second book, The Nature of Portland, will be on bookshelves in spring 2020.

Every summer brings pretty wildflowers to arid regions east of Bend, but this year is special. Like Southern California this spring, we’re witnessing a superbloom due to high snowfall and greater-than-average rainfall.

A friend who lives in Alfalfa, about 15 miles east of Bend, said, “I have never seen such a phenomenal wildflower season in 30 years, and it may be another 30 years before it happens again.”

You don't want to miss it. Head out this week to the Oregon Badlands Wilderness or other rocky, sandy areas east or north of Bend. Go early, or go late to avoid high temperatures. But go.

On BLM land yesterday, about 20 minutes east of Bend, the ground was carpeted in more threadleaf phacelia (Phacelia linearis) than I’ve ever seen before.

Threadleaf phacelia

Tucked under all those elegant purple flowers you’ll spot mound after mount of pink—those are cheerful dwarf monkeyflowers (Diplacus nanus).

Also look for pom-poms of very happy buckwheats (Eriogonum spp.), which as deeply drought-tolerant species, are probably getting more water than they know what to do with.

Sulphur-flower buckwheat. Photo: M.A. Willson

If you can’t get out to explore the high desert in the next week or so, keep trying. Yellow western groundsel (Senecio integerrimus) and Oregon sunshine (Eriophyllum lanatum) will be out in force, along with everyone’s favorite, green-banded mariposa lilies (Calochortus macrocarpus). If you go in the evening, also keep an eye out for night-blooming granite gilia (Linanthus pungens).

Green-banded mariposa lily. Photo: Ron Halvorson

M.A. Willson in her natural element.

Before I get all sentimental, here’s a tip: Go to mawillson.com for the best, most detailed information about where to hike, and when, to see wildflowers in Central Oregon. (Follow-up note: Sorry, folks, that site's no longer active.)

You’ll learn that you’re running out of time to hit Alder Springs, and that the last week in June is usually the best time to go to Coffin Mountain. She also details "the premier hikes in Central Oregon" that you should explore in August.

In all, M.A. Willson’s site features a dozen hikes near Bend, with ideas for the Columbia River Gorge and the Arctic too. Each destination includes more than a dozen photos of wildflowers you’ll see along the way, plus directions and tips for your trip.

That website—which she created simply as a gift to her fellow nature lovers—is how I met M.A. Willson six years ago. I ran across her site while researching The Nature of Bend, and asked M.A. if she might have wildflower photos she’d be willing to share. I thought maybe she’d donate a few, but she ended up providing more than 60, including many of the most spectacular photos in the book, and she lent her considerable expertise too.

Bitterroot, one of M.A.’s favorites.

More importantly, M.A. became a friend.

I should point out that she created that website when she was in her 70s, and she was well into her 80s before I met her. So, if you didn’t know her, maybe it won’t be a surprise to tell you that M.A. passed away last June, at the age of 87.

But if you did know her, maybe like me you can’t help but think she should still be heliskiing in Canada or rafting the Owyhee or gardening better than the rest of us.

On the last active day of her life, M.A. gave a talk about wildflowers to a packed house at Broken Top Bottle Shop. I remember how light on her feet she was that night, how on point and comfortable, and how she looked forward to her post-talk beer.

It was clear to the room full of friends, family, and strangers that she’d been everywhere, knew what you’d find on every trail, and had pretty photos of all the plants you might want to know.

At the end of her talk, she handed out laminated bookmarks of photos she'd taken over the years. Then she had that beer, and a good dinner too, before walking out of the restaurant and suffering a heart attack.

Beargrass is another of her favorite blooms.

Being M.A., she insisted on driving herself to the emergency room, where she spent the next week or so saying her goodbyes and making to-do lists for her daughter. She also told her book club which book they should read next.

Somehow or other, it’s June again, meaning a year has passed without M.A. in it. I can’t tell you how sad that makes me, but you know how it goes: There’s no stopping change, no slowing down time, no life without death. You can’t have the good side of nature, with all its beauty, and not have the rest of it.

To celebrate her life with me, please use her wonderfully generous website to explore Central Oregon’s best hikes. And in life, if not out on the trail, go ahead and leave a trace. Share what you find beautiful. Make friends every year of your life. Laugh so hard your body shakes and your eyes earn their wrinkles. Be a force of nature, like M.A.

Pronghorns are perhaps the most graceful animals native to the high desert of Central and Eastern Oregon. Golden Eagles are the most majestic, Greater Sage-Grouse the most emblematic.

And Burrowing Owls? They’re the funniest.

Five Burrowing Owls, Floridana, Florida. by Travelwayoflife, CC BY-SA 2.0

Let us never overlook the fact that we’re talking about owls who live in dark underground burrows. Not for them the trees that most other birds prefer. No, they move into holes in the ground excavated by prairie dogs, ground squirrels, skunks, and in our area, badgers.

The owls dig with their beaks and make dirt fly with their feet, reshaping old burrows to their liking and decorating them with cow manure, feathers, grass, and whatever else strikes their fancy (the manure is thought to attract insects for eating and might mask the owls' scent from predators).

The oddest of owls

Burrowing Owls’ predilection for the subterranean is not their only oddity. They also fly during the day as well as at night. And they don’t hoot; they coo (and warble, cluck, and scream). When threatened, they mimic the threatening hiss of a rattlesnake.

More unusual still are their legs. Imagine yourself as the designer of Burrowing Owls, holding a clump of brown clay in your hands. First, you shape the body to be about the size of a bulky American Robin—which is to say a quite small owl. But then you find yourself with lots of excess clay. What to do? You roll it into two extra-long cigars, each maybe four inches long, and attach them to the small bodies. There! Only the legs look naked, so you add some bloomer-like white feathers to their tops. Voila!

Those long legs are a smart adaptation that allows Burrowing Owls to stand tall like curious meerkats, peering this way and that across the broad expanses of grasslands and sagebrush country where they live. They also use their feathered stilts to speed across the ground chasing prey, their bodies thrust forward like a tourist on a Segway.

It’s actually not their long legs that make Burrowing Owls such a social media darling, subject of hundreds of memes and videos—or at least it's not solely their legs. It’s also their white unibrow, which, when lowered, makes them appear comically offended and, when raised, suggests the wide-eyed curiosity of a puppy.

Add to their expressive unibrow their body bobs, 180-degree head tilts to the left and right, and communal nature (with groups bobbing and tilting at once), and you start to understand why just about everyone loves a Burrowing Owl.

Adoration isn’t enough

Unfortunately, despite our affection for them, we’re not doing a great job of protecting these owls. It used to be you could get your truck’s grill cleaned by nesting Burrowing Owls while you used the facilities at the Brothers Oasis (the rest area in the tiny town of Brothers, Ore.).

But those owls, and countless others across the country, have been killed by people who were trying to kill something else: ground squirrels, in the case of the mating pair in Brothers. The sad irony is that Burrowing Owls are on the same side as landowners, regularly eating their fill of ground squirrels, pocket gophers, and other rodents.

Today, Burrowing Owls are considered “birds of conservation concern” both federally and in Oregon and seven other Western states. It’s not only poisoning and pesticides that are causing their declining populations but also (and perhaps mostly) habitat loss. They need flat, open territories: shrub-steppe and grasslands, ideally, or agricultural fields and pastures. In Oregon, they also need badgers to build their burrows.

Which brings us to public lands, which provide the natural habitat that Burrowing Owls and just about every other bird needs. Deepening protections of the wild lands of southeast Oregon, for instance, would help these owls and hundreds of other species. So would installation of artificial nest burrows and the addition of more habitat protection programs throughout Central and Eastern Oregon.

There’s nothing funny about the dangers facing Burrowing Owls, but the good news is that through the Oregon Natural Desert Association (ONDA) and other like-minded organizations, we can take action to ensure these odd little owls are still out there for a long time to come, cooing and hissing, bobbing and head-tilting, burrowing and bringing us joy.

Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany seeds and tails.

I wrote this blog about one of my favorite trees for the Oregon Natural Desert Association. ONDA is a local nonprofit that's absolutely tireless in their efforts to protect and defend the high desert of Central and Eastern Oregon.

You can view the story on ONDA's site—here. It's the first of a five-part series spotlighting species that depend on the habitats ONDA works to protect.

And here it is, reprinted for you, in case you'd rather not make that extra click.

Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany Trees live their lives on a different timescale than ours, so it helps to slow ourselves down to fully appreciate them. Certainly a shrubby little tree like curlleaf mountain-mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) isn't going to catch our eye if we're racing past along the trail. But take time for a closer look, and you'll probably be adding this one to your list of favorite trees in Central Oregon.

On the topic of timescales, consider that few of us will celebrate our 100th birthday, while at that age the slow-growing mountain-mahogany has barely begun. The tree doesn't reach its full height until about the century mark, and from there it can go on living for at least another 1,200 years. Such a long lifespan is especially remarkable given that the tree grows in some of our most inhospitable conditions: at elevation, often in drought conditions, and on highly exposed rocky ridges and buttes.

One key to the mountain-mahogany's long life is that it's a nitrogen fixer like peas and alders, which means that at least some individuals have bacteria-filled nodules on their roots that convert nitrogen into a usable, water-soluble form-basically, they manufacture their own fertilizer. That can help the trees survive harsh growing conditions, and it's also been shown to support the growth and vitality of the grasses and wildflowers that grow near them.

But let's get back to us out on the trail, slowing down to appreciate mountain-mahogany. If it's spring, stop first and listen for the hum of activity. Although the tree is mostly pollinated by the wind, it's also popular with a host of buzzing pollinators, including lots of native bees.

Step even closer to smell the tiny whitish-yellow trumpet flowers-they offer up one of the sweetest aromas you'll find on any of our native trees or shrubs. You can also see the stamens (male reproductive parts) sticking out well past the petals, like tiny arms with fistfuls of pollen that they're offering to the wind.

On warm summer days, scoop up and crush a handful of the inches-deep drifts of orange and rust-colored leaves that have fallen under the trees, and inhale deeply. Sometimes the leaves are too old or dried out and you won't smell much, but oh, when you get it just right-it's such a joy to discover a new scent (rather like a sweet tobacco) in an unexpected place, from a tree that few people even notice.

Late summer is the best time for simply looking at mountain-mahoganies because they'll be covered in seeds with one- to three-inch curly white tails trailing behind (the genus name, Cercocarpus, means "tailed fruit"). When the wind blows a seed from the tree, the feathery streamer helps it fly a little farther. Eventually the seed settles on the ground, with the streamer still attached and spiraled like a pig's tail. When it rains or gets humid enough, the spiral unwinds, effectively drilling the seed into the ground so it can germinate in the spring.

You can test this amazing process for yourself: Wet one of the wispy streamers and place it in your palm, then watch as it slowly straightens before your eyes.

To see (and smell and touch and listen to) curlleaf mountain-mahogany, head to Pine Mountain, the Dry River Canyon, or lots of other public lands that ONDA is working to protect.

Yes, yes, we're surrounded by beautiful singing migratory birds. But where's the love for those that never leave?

Read MoreFind out how to protect your backyard and garden from hungry deer.

Read MoreShould Oregon throw out the western meadowlark as our state bird?

Read MoreView a few of the first wildflowers you're likely to see this spring!

Read MoreYes, it's still snowing in Bend. But I promise spring is coming—and so are the bumblebees.

Read More