Finding Relief with Linnaeus

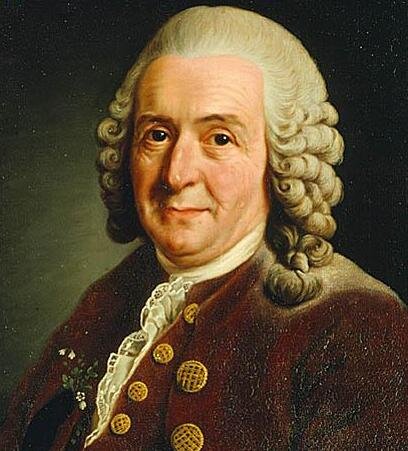

/Look, I know how nerdy this sounds, but Carl Linnaeus makes me laugh. Yes, I’m talking about the 18th century botanist most famous for coming up with the system we use to name plants and animals.

I’ve been doing some research into Linnaeus that has distracted me from reading more than necessary about the coronavirus, the global economy, political infighting, and toilet paper shortages.

I hope that these seven fascinating, strange, and flat-out funny stories about a quirky, misguided scientist will likewise give you a reprieve from the darker stories of the day.

1. Linnaeus hated amphibians. No, I mean, he really hated them.

Linnaeus did a helpful thing in coming up with binomial nomenclature, but he was a deeply, deeply flawed person and scientist. I highly recommend reading Jason Roberts's book Every Living Thing to learn more about Linnaeus and his skulduggery.

But in this little blog I'm focused on some of the funny stuff from Linnaues, so let's enjoy the fact that he described amphibians as “these most terrible and vile animals.” He listed their attributes as: “ghastly color, cartilaginous skeleton, foul skin, fierce face, a meditative gaze, a foul odor, a harsh call, a squalid habitat, and terrible venom.” See what I mean? He HATED amphibians.

2. Did I mention that Linnaeus hated amphibians?

An “unsightly” treefrog. Photo: Alan St. John

Linnaeus loved to categorize things (rather obviously, since that was his life's work), and he did so using some humorous analogies.

At one point he compares animals to an infantry: Mammals are foot soldiers dressed in furs, birds are cavalry beautifully clothed in dyed down. Amphibians? They're “an unsightly, hideous naked mob, with no uniforms, inadequately armed except some who got terrifying poisoned darts.”

To be fair, Linnaeus also wrote one nice thing about amphibians: “Some [frogs] sang so beautifully that you felt newborn, and banished all disagreeable thoughts; others so mournfully that one almost dies of melancholy.” On that, at least, I think he’s right.

3. Linnaeus named noxious weeds after his enemies.

Linnaeus was a dangerously vengeful man, but again, let's focus on the funny angle. A German named Johann Siegesbeck was offended by Linnaeus’s work, so in response to the German’s criticism, Linnaeus named a weed that produces a nasty-smelling fluid Siegesbeckia. Likewise, when a former student of Linnaeus’s named Daniel Rolander refused to show his full plant collection to Linnaeus (so rude!), Linnaeus named a species of beetle after him, Aphanus rolandri. Just to rub it in, Aphanus means “inconspicuous.”

4. Linnaeus was his own biggest fan.

Linnaeus wrote four—four!—autobiographies. In those days, autobiographies were sort of like résumés, so it wasn’t unusual to write one, or maybe two, but Linnaeus wrote four, in which he admired himself in myriad ways (using third person to refer to himself):

Of returning to his fiancée, after four years away: “Travelled straight to Falun to see his beloved, who for nearly four years had been waiting for her dear Ulysses.”

Of one of his works: “the foreigners will be stunned by it.”

Of another work: It will live “in the palace of the princes of botany.”

Of his other works: They’re “masterpieces.”

On his accomplishments: “No one has been a greater botanist or zoologist.”

5. His system for naming species has saved us a lot of time.

Before Linnaeus came up with the idea of naming things by genus and species, a wild geranium was called Geranium pedunculis bifloris caule dichotomo erecto foliis quinquepartitis incisis summis sessilibus. A particular tomato species was Solanum caule inerme herbaceo, foliis pinnatis incisis, racemis simplicibus.

I think we can agree that those names are not simplicibus at all. To make matters even more confusing, those same plants would often have entirely different names in other countries.

These naming issues increased in the 1730s, when people began to realize that the world had more than just a few thousand plant and animal species. As ships started traveling the world and returning to Sweden with “new” plant and animal species, it became evident that it was critical that we have one clear, simple naming system. That’s what Linnaeus came up with, and for that he’s justifiably renowned.

By the way, there were about 20,000 named species in Linnaeus’s time. Today there are more than 1.8 million.

6. Linnaeus’s grandmother was burned as a witch.

This is not so funny, but it is interesting. Unlike her famous grandson, Linnaeus’s grandma was not exactly rewarded for her interest in botany. Try as I might, I haven’t been able to learn anything more than the fact that she was a botanist who was burned as a witch. It makes you think, doesn’t it, about what more women in history might have accomplished if they’d been able to pursue their interests uninhibited by discrimination and acts of violence.

7. Linnaeus named Homo sapiens.

We can thank Linnaeus for thousands of scientific names that still apply today. Among them is the name of our own humble species (although he separated us into four species, distinguished by woefully wrong and racist traits). Homo means “male” and sapiens means “wise,” so the first word is true only half the time and the second is true rarely, if ever, as evidenced by Linnaeus himself.

The scary thing is I’m only warming up here. I’ll post part two on Linnaeus soon. As long as we’re self-quarantining, we might as well enjoy some laughs.