More Laughs with Linnaeus

/These are scary times we’re living in, and I’m finding that my requirements shift almost by the hour, from needing to soak up the latest facts to needing to “socially distance” myself from the news through laughter and silliness.

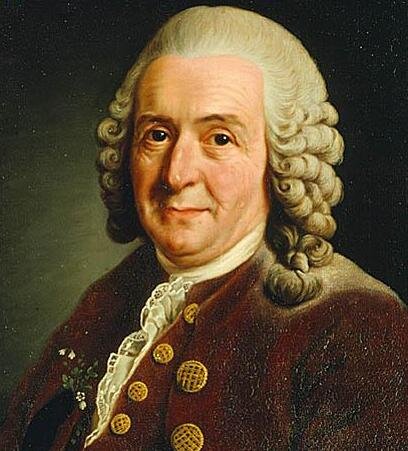

When and if you fall into the latter camp, this blog is for you. It’s a follow-up to my previous blog, where I listed some wonderfully odd and often humorous facts about Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish scientist and sometimes-awful human who came up with binomial nomenclature (naming species by a genus and species, like Canis lupus for wolves).

I’ll get back to talking about nature in a more direct way in future blogs, but for now I hope these eight stories provide a pleasant diversion.

1. Linnaeus had a lot to say about sex. A LOT.

Aristotle thought that since plants don’t move, they don’t have sex. Linnaeus put an end to that nonsense. He showed that flowers have sexual organs called pistils and stamens. “Yes, love comes even to the plants,” he wrote.

As Oliver Sacks put it, Linnaeus “made merry with the idea” of sexual organs in plants. Linnaeus wrote an essay called “Introduction to the Betrothal of Plants” and talked about stamens as husbands, pistils as wives, and the calyx as the nuptial bed. Here’s one of his steamy passages:

The flower’s leaves … serve as bridal beds which the creator has so gloriously arranged … and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much greater solemnity. When now the bed is so prepared, it is time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and offer her his gifts.

A trillium showing off its reproductive parts. Photo: M.A. Willson

As you might imagine, some people were titillated by all this plant sex talk, which led to an increased interest in botany (seriously). Also as you might imagine, other people clutched their pearls. One critic said, “Such loathsome harlotry as several males to one female would never have been permitted in the vegetable kingdom by the Creator.”

As it turns out, such “harlotry” is not only permitted but quite commonplace across the natural world.

2. Darwin’s grandpa was titillated by Linnaeus.

Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus was so inspired by Linnaeus’s ideas about the sex lives of plants that he penned a couple long poems published together as The Botanic Garden (1789). His book was a bestseller that created an uproar because of its sexually explicit passages. The book also included a hint of Erasmus’s belief in evolution, long before his grandson’s revelations on the subject.

Another favorite story about Erasmus: He was a doctor by trade but also a brilliant inventor of, among other things, a copying machine, a canal lift for barges, and a steering mechanism for carriages that was later adapted for cars.

But my very favorite invention? Erasmus grew so rotund that he had a semi-circle cut out of his place at the dinner table so he could sit closer to the food.

3. Linnaeus was confused about swallows.

In Oregon, we’ll soon see tree, cliff, and other swallows swooping and swerving over waterways. Where have they been since fall? We now know that they migrate south where there are insects to feed on through the cold months. But for his whole life, Linnaeus believed that swallows slept through winter at the bottom of lakes.

Barn swallow. Photo: John Williams

More specifically, Linnaeus believed that swallows gathered in large groups, then dove under a sheet of ice where they slept, gills be damned, until spring came along and they thawed out. This was common folklore at the time, as it seemed impossible that birds could fly thousands of miles twice a year—which is, indeed, an astounding feat.

4. Linnaeus had many other odd and wrong-headed beliefs.

Linnaeus knew more about plants than he did about animals, and despite his claims to fame, he was a pretty crummy scientist overall. Case in point: Obviously without evidence, he thought that you could turn a puppy into a dwarf by rubbing the puppy’s back with a flavored spirit called aquavit. If you’re really, really bored during the pandemic, you’re free to try this.

Linnaeus also thought that rattlesnakes used the intensity of their gaze to bewitch birds and squirrels, causing them to fall from trees into the snake’s mouth.

5. Linnaeus gave us “fauna.”

Linnaeus was the first to use the word fauna (meaning animals) as the counterpart to flora (plants). Fauna is a feminine version of Faunus, the name of a Roman forest god.

6. Sweden loves Linnaeus.

Linnaeus is a beloved national hero in Sweden, where his face is on the 100 kronor note and his favorite flower, the twinflower (Linnaea borealis), appears on the 20 kronor note. If you read the first blog, you won’t be surprised to hear that Linnaeus named twinflower after himself.

7. Linnaeus was first to use the symbols for male and female.

The circle with the arrow for male and the circle with a cross below it for female? You can thank Linnaeus for them. The symbols had been used by chemists (the male symbol referred to Mars and iron; the female to Venus and copper), but Linnaeus was the first to use them as symbols for male and female species.

8. Linnaeus lied about his travels.

In 1732, when Linnaeus was 25, he traveled from Uppsala, near Stockholm, to an area called Swedish Lapland, the northernmost region of Sweden. He kept a detailed, illustrated journal of the plants and animals he saw on his five-month trip.

When he got back to Uppsala, Linnaeus exaggerated the whole experience. First, he said he had traveled 4,500 miles, which was about double the miles he actually traversed. The poor and famously stingy Linnaeus was being paid by the mile, so that might be why he drew an entirely fictionalized inland leg on his map.

Linnaeus also exaggerated the hardships he endured on his epic journey. A historian named Lisbet Koerner estimates that Linnaeus only spent 18 days of his five-month journey sleeping outside homes or on the coast. Which reminds me of Henry David Thoreau, whose “hardships” at Walden Pond included having his mom do his laundry and bring him sandwiches.

That’s all for now, folks. Please take care of yourself during this difficult time, and spread love to others however you can.